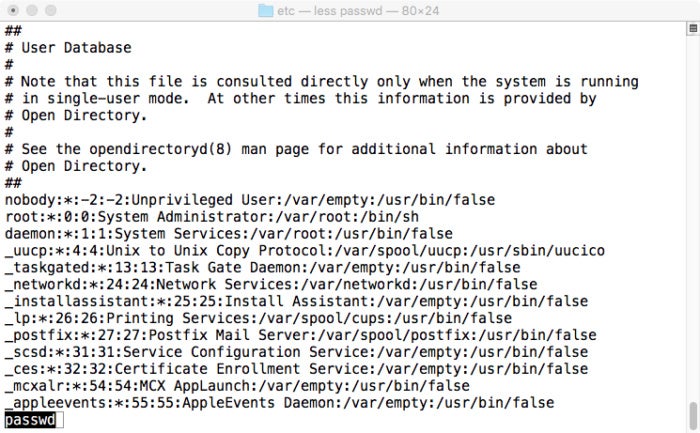

A man page (short for manual page) is a form of software documentation usually found on a Unix or Unix-likeoperating system. Topics covered include computer programs (including library and system calls), formal standards and conventions, and even abstract concepts. A user may invoke a man page by issuing the mancommand.

By default, man typically uses a terminal pager program such as more or less to display its output.

The Linux Programmer’s Guide is meant to do what the name implies— It is to help Linux programmers understand the peculiarities of Linux. By its nature, this also means that it should be useful when porting programs from other operating systems to Linux. Therefore, this guide must describe the system calls and the major kernel.

Because man pages are distributed together with the software they document, they are a more favourable means of documenting software compared to out-of-band documentation like web pages, as there is a higher likelihood for a match between the actual features of the software to the documented ones.[1]It is for this reason that man-pages are often referred to as an on-line or online form of software documentation,[2] even though the man command does not require internet access, dating back to the times when printed out-of-band manuals were the norm.

History[edit]

In the first two years of the history of Unix, no documentation existed.[3] The Unix Programmer's Manual was first published on November 3, 1971. The first actual man pages were written by Dennis Ritchie and Ken Thompson at the insistence of their manager Doug McIlroy in 1971. Aside from the man pages, the Programmer's Manual also accumulated a set of short papers, some of them tutorials (e.g. for general Unix usage, the C programming language, and tools such as Yacc), and others more detailed descriptions of operating system features. The printed version of the manual initially fit into a single binder, but as of PWB/UNIX and the 7th Edition of Research Unix, it was split into two volumes with the printed man pages forming Volume 1.[4]

Later versions of the documentation imitated the first man pages' terseness. Ritchie added a 'How to get started' section to the Third Edition introduction, and Lorinda Cherry provided the 'Purple Card' pocket reference for the Sixth and Seventh Editions.[3] Versions of the software were named after the revision of the manual; the seventh edition of the Unix Programmer's Manual, for example, came with the 7th Edition or Version 7 of Unix.[5]

For the Fourth Edition the man pages were formatted using the troff typesetting package[3] and its set of -man macros (which were completely revised between the Sixth and Seventh Editions of the Manual,[4] but have since not drastically changed). At the time, the availability of online documentation through the manual page system was regarded as a great advance. To this day, virtually every Unix command line application comes with a man page, and many Unix users perceive a program's lack of man pages as a sign of low quality; indeed, some projects, such as Debian, go out of their way to write man pages for programs lacking one. The modern descendants of 4.4BSD also distribute man pages as one of the primary forms of system documentation (having replaced the old -man macros with the newer -mdoc).

Few alternatives to man have enjoyed much popularity, with the possible exception of GNU Project's 'info' system, an early and simple hypertext system.In addition, some Unix GUI applications (particularly those built using the GNOME and KDE development environments) now provide end-user documentation in HTML and include embedded HTML viewers such as yelp for reading the help within the application.

Man pages are usually written in English, but translations into other languages may be available on the system.

The default format of the man pages is troff, with either the macro package man (appearance oriented) or mdoc (semantic oriented). This makes it possible to typeset a man page into PostScript, PDF, and various other formats for viewing or printing.

Most Unix systems have a package for the man2html command, which enables users to browse their man pages using an HTML browser (textproc/man2html on FreeBSD or man on some Linux distribution).

In 2010, OpenBSD deprecated troff for formatting manpages in favour of mandoc, a specialised compiler/formatter for manpages with native support for output in PostScript, HTML, XHTML, and the terminal.

In February 2013, the BSD community saw a new open source mdoc.su service launched, which unified and shortened access to the man.cgi scripts of the major modern BSD projects through a unique nginx-based deterministic URL shortening service for the *BSD man pages.[6][7][8]

There was a hidden easter egg in the man-db version of the man command that would cause the command to return 'gimme gimme gimme' when run at 00:30 (a reference to the ABBA song Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midnight). It was introduced in 2011[9] but first restricted[10] and then removed in 2017[11] after finally being found.[12]

Command usage[edit]

To read a manual page for a Unix command, a user can type:

Pages are traditionally referred to using the notation 'name(section)': for example, ftp(1). The section refers to different ways the topic might be referenced - for example, as a system call, or a shell (command line) command or package, or a package's configuration file, or as a coding construct / header.

The same page name may appear in more than one section of the manual, such as when the names of system calls, user commands, or macro packages coincide. Examples are man(1) and man(7), or exit(2) and exit(3). The syntax for accessing the non-default manual section varies between different man implementations.

On Solaris and illumos, for example, the syntax for reading printf(3C) is:

Linux Programmer's Manual Versus Bsd System Call Manual On Mac Windows 10

On Linux and BSD derivatives the same invocation would be:

Linux Programmer's Manual Versus Bsd System Call Manual On Mac Computer

which searches for printf in section 3 of the man pages.

Manual sections[edit]

The manual is generally split into eight numbered sections, organized as follows (on Research Unix, BSD, macOS and Linux):

| Section | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | General commands |

| 2 | System calls |

| 3 | Library functions, covering in particular the C standard library |

| 4 | Special files (usually devices, those found in /dev) and drivers |

| 5 | File formats and conventions |

| 6 | Games and screensavers |

| 7 | Miscellanea |

| 8 | System administration commands and daemons |

Unix System V uses a similar numbering scheme, except in a different order:

| Section | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | General commands |

| 1M | System administration commands and daemons |

| 2 | System calls |

| 3 | C library functions |

| 4 | File formats and conventions |

| 5 | Miscellanea |

| 6 | Games and screensavers |

| 7 | Special files (usually devices, those found in /dev) and drivers |

On some systems some of the following sections are available:

| Section | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | |

| 9 | Kernel routines |

| n | Tcl/Tk keywords |

| x | The X Window System |

Linux Programmer's Manual Versus Bsd System Call Manual On Mac Pc

Some sections are further subdivided by means of a suffix; for example, in some systems, section 3C is for C library calls, 3M is for the math library, and so on. A consequence of this is that section 8 (system administration commands) is sometimes relegated to the 1M subsection of the main commands section. Some subsection suffixes have a general meaning across sections:

| Subsection | Description |

|---|---|

| p | POSIX specifications |

| x | X Window System documentation |

Some versions of man cache the formatted versions of the last several pages viewed.

Layout[edit]

All man pages follow a common layout that is optimized for presentation on a simple ASCII text display, possibly without any form of highlighting or font control. Sections present may include:

- NAME

- The name of the command or function, followed by a one-line description of what it does.

- SYNOPSIS

- In the case of a command, a formal description of how to run it and what command line options it takes. For program functions, a list of the parameters the function takes and which header file contains its declaration.

- DESCRIPTION

- A textual description of the functioning of the command or function.

- EXAMPLES

- Some examples of common usage.

- SEE ALSO

- A list of related commands or functions.

Other sections may be present, but these are not well standardized across man pages. Common examples include: OPTIONS, EXIT STATUS, RETURN VALUE, ENVIRONMENT, BUGS, FILES, AUTHOR, REPORTING BUGS, HISTORY and COPYRIGHT.

Authoring[edit]

Manual pages can be written either in the old man macros, the new doc macros, or a combination of both (mandoc).[13] The man macro set provides minimal rich text functions, with directives for the title line, section headers, (bold) fonts, paragraphs and adding/reducing indentation.[14] The newer mdoc language is more semantic in nature, and contains specialized macros for most standard sections such as program name, synopsis, function names, and the name of the authors. This information can be used to implement a semantic search for manuals by programs such as mandoc. Although it also includes directives to directly control the styling, it is expected that the specialized macros will cover most of the use-cases.[15]

See also[edit]

- ManOpen – NeXT/macOS graphical man utility

References[edit]

- ^der Mouse (2019-03-30). 'Web 'documentation' [was Re: Removing PF]'. tech-kern@NetBSD (Mailing list). NetBSD. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^'man(1) — display online manual documentation pages'. BSD Cross Reference. FreeBSD. Retrieved 2019-04-01. Lay summary.

The man utility finds and displays online manual documentation pages.

- ^ abcMcIlroy, M. D. (1987). A Research Unix reader: annotated excerpts from the Programmer's Manual, 1971–1986(PDF) (Technical report). CSTR. Bell Labs. 139.

- ^ abDarwin, Ian; Collyer, Geoffrey. 'UNIX Evolution: 1975-1984 Part I - Diversity'. Retrieved 22 December 2012. Originally published in Microsystems5(11), November 1984.

- ^Fiedler, Ryan (October 1983). 'The Unix Tutorial / Part 3: Unix in the Microcomputer Marketplace'. BYTE. p. 132. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^Pali, Gabor, ed. (12 May 2013). 'FreeBSD Quarterly Status Report, January-March 2013'. FreeBSD. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^Murenin, Constantine A. (19 February 2013). 'announcing mdoc.su, short manual page URLs'. freebsd-doc@freebsd.org (Mailing list). Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^Murenin, Constantine A. (23 February 2013). 'mdoc.su — Short manual page URLs for FreeBSD, OpenBSD, NetBSD and DragonFly BSD'. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^''GIT commit 002a6339b1fe8f83f4808022a17e1aa379756d99''. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^''GIT commit 84bde8d8a9a357bd372793d25746ac6b49480525 ''. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^''GIT commit b225d9e76fbb0a6a4539c0992fba88c83f0bd37e ''. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^''Why does man print 'gimme gimme gimme' at 00:30?''. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^

groff_tmac(5)– Linux File Formats Manual - ^

man(7)– Linux Miscellanea Manual - ^

mdoc(7)– FreeBSD Miscellaneous Information Manual

External links[edit]

- History of UNIX Manpages for a primary-source history of UNIX manpages.

- UNIX and Linux Man Page Repository with nearly 300,000 well formatted man pages.

This article is based on material taken from the Free On-line Dictionary of Computing prior to 1 November 2008 and incorporated under the 'relicensing' terms of the GFDL, version 1.3 or later.